Part 2 of this article pair on the space programs of ASEAN focuses on Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, and Vietnam. To read about space initiatives in Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia and Malaysia, head to Part 1.

Myanmar

In contrast to some ASEAN powers and despite a considerable size, Myanmar has, until recently, not engaged in space exploration. With the lowest GDP per capita in ASEAN and chronic government instability, Myanmar tended to pursue development in other fields, and mostly purchased ]usage rights for communications and remote imagery from Intelsat, China, India, and Japan. This is however evolving as the space industry is taking an increasingly salient position in economic development.

The founding of a specialized Myanmar Aerospace Engineering University in 2002 demonstrates the country’s commitment to talent development in the sector. The first signs of Burmese participation in space activities emerged in 2017, as the country established a steering committee aiming to found a space agency and indigenously develop a satellite of its own. Chaired by then Vice-President Myint Swe, the committee acknowledged the high costs of building a satellite, and partnered with Hokkaido University in Japan in 2018.

The project came to fruition in 2021, with the launch of Lawkanat-1, Myanmar’s first satellite. Lawkanat-1 is a 50kg microsatellite that was deployed from the International Space Station, though not before being held up on board after the 2021 Myanmar coup. Lawkanat-1’s mission ended in April 2023, and the Myanmar Government continues collaborating with Hokkaido University to launch a second microsatellite in 2023.

Philippines

The Philippines has emerged as a late-entrant player in the Southeast Asian space scene, with a history of false starts in its space initiatives prior to 2013. One notable setback was the establishment of PhiliComSat in 1966, which aimed to represent the Philippines in global satellite organizations but was plagued by corruption and mismanagement. The Supreme Court eventually intervened to address the issues surrounding the company. In the early 1970s, the secretive Santa Barbara project worked on developing and testing the Bongbong rocket. However, the program was abruptly discontinued in 1972 for undisclosed reasons. In 2012, Representative Angelo Palmones proposed a bill to establish a space agency for the Philippines, but it died at the committee stage due to poor timing with the 2013 general elections, and a popular sentiment that such a program would represent a waste of resources for the developing economy.

Entering the Game

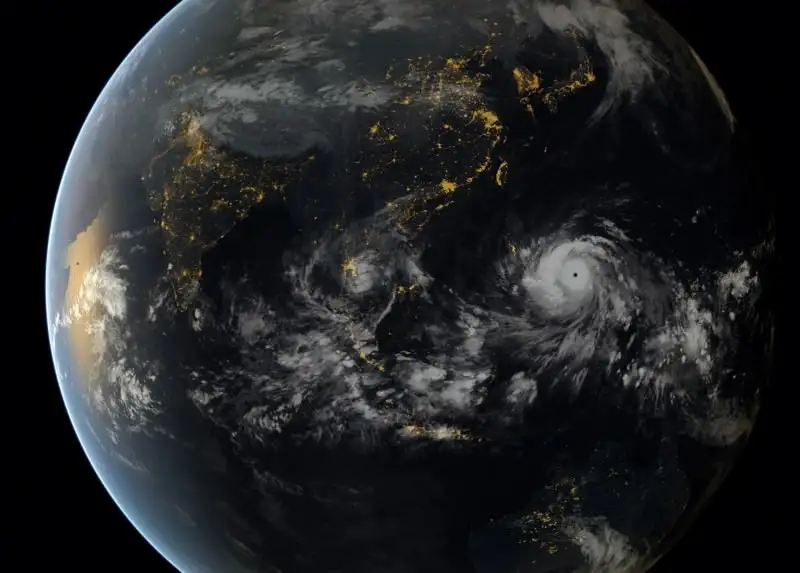

However, a turning point came in 2013 following the devastating Typhoon Haiyan, which underscored the critical need for earth imagery in disaster prevention. In response, the Philippines launched the Philippine Scientific Earth Observation Microsatellite program in 2014, collaborating with the Japanese universities of Hokkaido and Tohoku. Notably, the Diwata microsatellites, Diwata 1 (2016) and Diwata 2 (2018), captured images of disaster-affected areas and included a radio payload for enhanced communication during relief efforts.

The momentum continued with the signing of the Philippine Space Act of 2019, which established the legislative instruments for the creation of a Philippine Space Agency and a comprehensive Space Policy. The Philippine Space Development and Utilization Policy focuses on six key development areas: national security, hazard management, space research, industry capacity building, education and awareness, and international cooperation.

Looking ahead, the future of the Philippine Space Program is promising. The country is exploring satellite programs, aiming to develop an indigenous rocket using 3D printed materials, and forging partnerships with other spacefaring nations. While the Philippine Space Agency has rapidly developed itself, it faces an uncertain future full of opportunities and threats due to its quick formation without an institutional history. Nonetheless, it serves as a model for how a developing state can swiftly establish itself as a significant player in space exploration and utilization.

Singapore

Singapore, although not a traditional space power, has adopted a unique strategy in the space domain. Rather than competing with larger spacefaring nations, Singapore is focusing on growing a thriving commercial space sector and establishing itself as a hub for private-sector satellite manufacturers and operators. The country’s space journey began with the launch of its first fully indigenous satellite, the eXperimental-SATellite (X-SAT), in April 2011. Developed by the Nanyang Technological University (NTU), this microsatellite featured a multispectral camera and telecommunications channels.

In December 2015, Singapore achieved another milestone with the launch of TeLEOS-1, its first commercially developed satellite. Building on this success, Singapore rolled out TELEOS-2 on April 22, 2023. TELEOS-2 aims to further enhance, Singapore’s monitoring capabilities, paving the way for monitoring shipping routes by providing day and night images that could penetrate cloud cover. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) launched both satellites.

Atypical actors

Singapore’s space development is primarily driven by universities and the private sector, distinguishing it from many other countries. The NTU has been at the forefront, creating a series of increasingly smaller satellites, including picosatellites and microsatellites, in collaboration with the Kyushu Institute of Technology. The smallest, launched in 2014, weighs 193 grams and is the size of a phone. Singapore maintains launch partnerships with various space agencies such as ISRO, Arianespace, and JAXA.

Furthermore, Singapore’s status as a financial hub has attracted regional headquarters for space companies and startups. It hosts offices for prominent players like Vanuatu-based Pacific broadband provider Kacific, Emirati operator Thuraya, and SES’ only Asia-Pacific office, emphasizing its role as a commercial hub for the space sector. Singapore’s ambitions lie in building an industry-led and commercially viable space sector, with limited government involvement. Rather than aspiring to become a global space power, Singapore seeks to solidify its position as a hub for the commercial space industry, leveraging its strengths in finance, innovation, and technology.

Thailand

Thailand’s journey in space exploration began with the establishment of its ground station in 1982, becoming the first country in the region to receive and utilize data from the NASA ERTS-1 Programme. Thailand’s space endeavors gained momentum in 1993 when it financed its first satellite, Thaicom 1, a groundbreaking communications satellite built by Hughes Aircraft Company and launched on a French Ariane rocket. Between 1994 and 2016, Thailand continued to develop and launch eight more Thaicom satellites, collaborating with renowned international partners such as Northrop Grumman, Thales, Arianespace, and SpaceX. In November 2000, the Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA) was founded, becoming the driving force behind Thailand’s space exploration initiatives.

Thailand’s space program achieved remarkable milestones, including the successful launch of the country’s first earth observation satellite, THEOS-1, in 2008. Built by Airbus and launched from Russia, THEOS-1 played a crucial role in collecting high-resolution imagery of Earth’s surface. Soon to be succeeded by THEOS-2, also developed by Airbus, Thailand is poised to harness groundbreaking ground resolution capabilities of approximately one meter.

Building Indigenous Capacities

The nation celebrated a significant breakthrough in 2018 with the launch of its first fully Thai-built satellite, KNACKSAT. Developed by a dedicated university team from King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok (KMUTNB), KNACKSAT is a compact 1.3kg Cubesat that was successfully deployed into space aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. In 2019, Thailand further showcased its prowess by developing JAISAT 1, an amateur radio microsatellite developed by the Radio Amateur Society of Thailand.

Thailand’s space program has its sights set on remarkable future endeavors. The country’s commitment to space exploration extends to military applications, exemplified by the commissioning of NAPA-1 and NAPA-2, two military earth observation satellites by the Royal Thai Air Force. Moreover, the establishment of Mu Space, led by visionary entrepreneur James Yenbamroong, marks a significant milestone in indigenous satellite production, enabling Thailand to scale up its capabilities and contribute to the growth of the space industry. The Kingdom also aims to launch a satellite into the moon’s orbit by 2027. In February 2023, Thailand and South Korea signed an agreement to study the feasibility of a Thai spaceport,

Supporting these aspirations, the Thai Government approved The National Space Master Plan (2023-2037) in December 2022. This comprehensive roadmap will guide the development of a space economy, emphasizing security, prosperity, and sustainability through research, innovation, technology, and exploration

Vietnam

Vietnam’s space program boasts a rich history of exploration, dating back to its participation in the Interkosmos program as an ally of the USSR in 1980. Notably, Vietnam achieved a significant milestone during this period by sending Pham Tuan to Salyut 6, making him the first Asian to venture into space. Despite the halt in spaceflight activities following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Vietnamese scientists continued to make breakthroughs in remote sensing until 2006.

A turning point came in 2006 when the Prime Minister approved the “Strategy for Research and Application of Space Technology Until 2020.” This marked a pivotal moment for Vietnam as it expanded its network of partners and focused on satellite development. In 2008, Vietnam acquired its first telecommunications satellite, VINASAT-1, built by Lockheed Martin and launched on an Ariane rocket. Subsequently, VINASAT-2, another Lockheed Martin satellite, was successfully placed into orbit by Ariane.

Vietnam further strengthened its space capabilities with the acquisition of VNREDSat-1, an Airbus-built earth observation satellite, in May 2013. The country also launched its first indigenous satellite, PicoDragon, weighing just 1 kg, in November 2013. This satellite, designed by engineers at the Vietnam National Space Center (VNSC), laid the foundation for future indigenous projects.

A Partnerships Hub

Cooperation with India became prominent in 2016 when Vietnam signed an inter-governmental agreement for peaceful space exploration. This collaboration included the construction of an ISRO tracking and imaging center in southern Vietnam. While raising speculations about potential military and political dimensions, this facility positioned Vietnam at the forefront of space activities in the geopolitically tense South China Sea.

Vietnam continued its pursuit of indigenous satellite development with the successful launch of MicroDragon, a 50 kg satellite designed by Vietnamese engineers in collaboration with Japanese universities, in January 2019. However, Vietnam faced a setback in November 2021 when it failed to establish contact with the Nanodragon, a 3.8 kg satellite launched by JAXA.

Partnerships remain crucial for Vietnam’s space program, as evidenced by the collaboration with Airbus for the construction of VNREDSat-2 and technology transfers in 2021. Additionally, NEC, a Japanese IT firm, has been contracted to design LOTUSat-1 and LOTUSat-2, radar earth observation satellites aimed at enhancing natural disaster prevention. Vietnam outlined its space future in the “Strategy of Space Science and Technology Development and Application to 2030,” which maintains a strong focus on satellite-based advancements.

Conclusion

ASEAN space programs feature a varied set of histories, means, and goals reflecting the region’s diversity. Nevertheless, each of those programs share common points, suggesting the possibility for deepened collaboration in the form of a common space agency.

Similar Aims for Space Programs of ASEAN

Space programs of ASEAN tend to follow a similar early path, first prioritzing communications satellites, before turning to earth observation satellites. The cost of purchasing a large communications satellite from a foreign manufacturer, combined with the cost of launch, results in a hefty price tag, often in the eight figures. Those costs are nevertheless offset by the savings of not needing to pay regular fees for the use of transponders on foreign satellites.

Most space programs of ASEAN seek to develop indigenous satellite building capabilities. This comes at a cost that the smaller economies of Brunei, Cambodia, and Laos are unable to bear. For the others, developing indigenous satellites is synonymous to the cultivation of a talent pool. In fact, most indignous satellites are smallscale cube sats developed in universities and research institutions. They also carry implications for the development of a commercial space industry in the future. Whereas Indonesia has begun research on developing a launch vehicle, and Thailand has begun to evaluate the value of building a spaceport, most ASEAN states do not seek to develop indigenous launc capacities on their own, recognizing the significant financial and time costs this would entail. ASEAN states work with limited an cruinized budgets, and therefore value programs that provide tangible benefits for their development efforts.

A focus on Astrodiplomacy

The other constant across member states is a focus on international collaboration. In many ways, it is inevitable: without launch capacities, satellite building states must collaborate with launchers, whether from the United States, Japan, Russia, China, India, or France. Collaboration however extends deeper, encompassing financing, design, data sharing, technology transfers, training, ground monitoring, and more.

ASEAN states diversiy their partners. Whereas the ideological leanings of each government determine the range of acceptable partners, most space programs of ASEAN feature partnerships with several large and established space powers. ASEAN states leverage the regional great power competition between Japan, China, and India to secure advantagous partnerships that advance their spacefaring capacities.

Challenges remain for the region’s space sector. Budgets are tight, and space powers are reluctant to transfer more sensitive technologies, especially related to advanced manufacturing and ballistic technology required for launch vehicles. The opportunity cost of space remain an issue government must address to justify the expense, as seen in the Philippines, where a 2012 bill to kickstart a space agency failed due to investment effectiveness concerns. Whereas states in the region have turened towards the outside for assistance, the growth of space programs in each state will transform neighbous into potential partners and raise the possibility of more intra-ASEAN partnerhips. For more information on efforts and the map of interests for creating an ASEAN space program, read this article.