This story could have been fiction – the story of how a tiny island nation attempted to build a space Empire, starting as a David and Goliath tale involving the U.S., China, a mad scientist, a princess, and more recently a Supreme Court. The story of Tongasat is however true and rings as an eerily prescient and cautionary tale for a phenomenon that will become increasingly familiar. This unique chain of events also highlights the need for a more collaborative and robust international space governance. Read more about how orbital slots work here.

Exposition: Why it All Happened

This unlikely story begins in 1987 with Dr Matt Nilson, an American engineer who had spent the better part of his career in the burgeoning commercial satellite industry. By the late 1970’s, he had gathered experience from stints at the U.S. publicly-owned telecommunications firm COMSAT and the satellite giant INTELSAT. Nilson was also an entrepreneur; from 1979, he offered business consulting services under the name of Nilson Research Corporation. In the early 1980s, he founded and ran Advanced Business Communications Inc (ABCI), which sought to offer satellite transponder rental services. By 1985, he had failed to obtain authorization from the U.S.’ Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and lost his main business partner. After his wife passed away, Nilson looked for a peaceful place to retire.

He chose the Kingdom of Tonga, a South Pacific archipelago with a surface smaller than that of New York City and a population struggling to reach 100,000. Tonga appeared like the ideal venue for Nilson to carry out his plan to “do nothing for a while”. By his admission, though, “it didn’t work that way.”

How Tongasat Began

Instead, given the Kingdom’s minute population, the satellite expert quickly met the archipelago’s royals: first, Princess Salote Mafile’o Pilolevu Tuita, and later, her father, King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV. The Monarch sought solutions for his country’s patchy communications, while Nilson saw a way to overcome the bureaucratic obstacles that had thwarted his ambitions. In April 1988, Tonga founded the Friendly Islands Satellite Communications Ltd, also known as Tongasat, in a bid to upgrade Tonga’s communications infrastructure. Nilson and another associate each got a 20 percent stake, the King reserved himself another 20 percent stake, and the remaining 40 percent went to Princess Pilolevu.

This story could have ended here – instead, it is where it truly begins. Satellites need a physical spot and a radio frequency to communicate with earth, and each frequency can accommodate 180 satellites. When in the early 1990s, Tongasat applied to the ITU for orbital slots (a process explained in more detail here), the tiny archipelago did not request one or two slots, but a staggering 16.

When Tongasat Shocked the World

Tonga’s claim stirred the small world of satellite insiders for several reasons. Firstly, the claim appeared disproportionate: how many satellites did a nation of 100,000 really need? Secondly, the market was occupied by established players while Tonga was a relative newcomer. Thirdly, the established players had imposed “gentlemen’s agreements” on claiming slots, one of which stipulated that slots should only be claimed if they were going to be used. Tonga’s tiny size, complete with a GDP of a few dozen million dollars and a non-existent space industry, made it evident that it would never fill these spots itself.

Nilson’s plan was to rent the slots at $2 million each, violating the spirit of the ITU by creating a speculative market in space. Lastly, Tongasat was claiming the last available slots over a highly-sought after position: satellites on those slots above the Pacific ocean could simultaneously service East Asia and the United States.

Early Space Diplomacy

Established players complained to the ITU. Intelsat and Columbia Communications, two satellite giants, claimed that Tonga’s attempt at warehousing and creating a marketplace for orbital slots violated the ITU’s rules. Intelsat’s Director General declared that it ”would set a dangerous precedent if not effectively challenged.” As challenges mounted, Nilson signed clients: first Unicom, and then U.S. satellite operator Rimsat. The latter responded to complaints by accusing Columbia and Intelsat of engaging in gatekeeping and anti-market practices. Australia also filed a complaint, expressing concern that Tonga’s claim “would make it impossible for larger economies to get enough Pacific Ocean slots.” The ITU, straddled between protecting the interests of established players and allowing free access to space for smaller entities, struck a compromise. In 1991, Tonga obtained 6 slots.

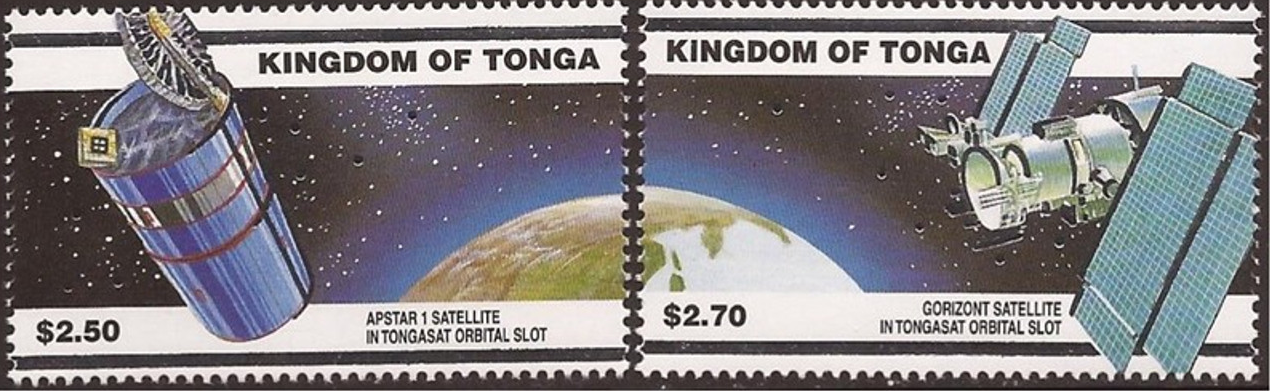

In 1996, a Hong Kong-based operator owned by the government of the People’s Republic of China known as APT Satellites became a Tongasat client. The deal triggered discussions of Sino-Tongan space co-operation. It is likely not a coincidence that, less than two years later, in 1998, Tonga formally ceased to recognise the Republic of China (Taiwan) and switched its recognition to Beijing.

Tongasat’s Downfall

Ethical issues triggered Nilson’s downfall: while leading Tongasat, he purchased 11.25% of Rimsat’s shares and became a director, even though they were a Tongasat client. Combined with suspicious behaviour during audits and misunderstandings of what constituted company expenses, this was enough for Princess Pilolevu to dismiss Nilson in February 1994.

Even after the ITU’s blessing and the backing of an emerging superpower, the absence of enforcement in space led to disputes and a “might makes right” approach. In 1997, Indonesian privately-owned operator Pacifik Satellite Nusantara (PSN) jammed a Tongasat satellite over a slot dispute. In 2006, Beijing itself took advantage of the situation when it launched a satellite into a Tongan slot without permission, effectively poaching the slot. Nilson was a competent scientist and a skilled businessman, but he did not anticipate that tiny Tonga had no way to ensure the payment of its $2 million rents. Arguably, political and diplomatic factors were Tongasat’s single most imposing hurdle.

Tongasat’s Lost Millions

In 2008 and 2011, China eventually compensated Tonga to the tune of $50 million earmarked as development aid, and wired the money to the Tongan Prime Ministers’ Office. $46.4 million were then wired to Princess Pilolevu’s bank account, and vanished thereafter.

In 2014, Prime Minister ‘Aksili Pohiva won the elections for Tonga’s Premiership. Pohiva was a somewhat provocative figure in the small kingdom: he had been a pro-democracy activist, was charged and found innocent of sedition in 2002, and was the first elected commoner Prime Minister. With a history of skepticism for the royal family, Pohiva sued Tongasat, claiming that Tongasat and Princess Pilolevu diverted China’s development aid for personal gain. When the Supreme Court agreed, Pohiva doubled down and claimed the entirety of Tonga’s Parliament should be jailed for not stopping this sooner. Although the Court awarded the Tongan government damages, the money is still nowhere to be found.

What we can Learn

Tongasat still operates to this day, leasing slots to Chinese companies. Nilson’s grand strategy of making Tonga a pacific space power and a global satellites hub fell to financial scandals, but more importantly to a lack of solid international governance and political awareness, both within Tongasat and amongst the spacefaring community. The tale of Tongasat is, in many ways, prescient: it highlights the need for transparent space rules and the protection of assets, underlines the growing challenge of orbital slot shortages, and presses on the absence of international enforcement of space rules. Tongasat demonstrated how unprepared the space scene was, and serves as a cautionary tale for governments and investors with an interest in space: politics matter.